The Assateague Indians: What Became Of Them

In the beginning the Assateague Indians were friendly, but it was not long before their attitude changed, as European newcomers began to covet the lands

by Suzanne Hurley

Colonel Edward Scarburgh, one of the first Indian fighters, was obsessed with the desire to rid this Maryland-Virginia area of all Indians at any cost, legally or illegally, and he devised an unfair and vindictive policy in regard to them. Although a Virginian, he served on some Maryland commissions and requested aid of the Maryland authorities in his campaign. When the Maryland officials refused his request, he set up a personal mission hoping to lead 300 footmen and 60 horses in an attack. However, as he noted in one of his report, the Assateagues "were harder to find than to conquer." The Scarburgh campaign was known as the "Seaside War" of 1659.

In 1662 Maryland made a treaty with the Assateagues (and the Nanticokes) whereby every white man that took land in Indian territory was to give the Indian emperor six match coats (garments made of a rough blanket or frieze, heavy rough cloth with uncut nap on one side). The emperor was also to receive a match coat for every runaway slave returned. The treaty further stated that no murders were to be committed by either side, that no Englishmen were to enter Indian territory without a pass, and that the Indians were not to trade with the Dutch to the north in Delaware so long as the English could supply their necessities.

This did not prevent Colonel Scarburgh from making plans to exterminate them, nor did it give them protection from the roving bands of Indians from the north.

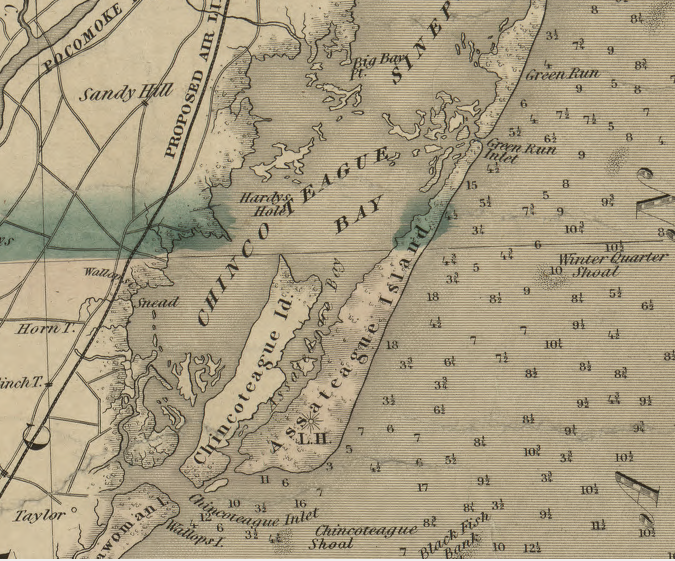

Several other treaties were signed between Maryland and the Assateagues before the close of the seventeenth century. One which ordered the Assateagues onto five reservations along the Pocomoke was signed by AMONUGUS, as Emperor of the Assateagues. And from the signatures of the 1678 treaty, it seems that the Emperor of the Assateagues held a dominant position over the Chincoteague king and kings of the Pocomoke River tribes.

Sessions of the Maryland General Assembly during this period recorded numerous complaints by the Assateague, stating that the colonists were letting their cattle into the cornfields, breaking the Indian's traps, cutting their timber and usurping (taking possession without authority) their lands."

The Assateagues complained in 1686 that several English men had encroached upon the Indian land and had even built homes in the town where the Indians lived. They complained that one man in particular, EDWARD HAMMOND, was an encroacher and that he had stolen great quantities of Roanoke (Indian money) and skins from the tombs of former Indian kings. The Roanoke and skins had been offerings to the dead. They asked that something be done about Hammond and that provisions be made so that the Indians could live without disturbance and encroachment by the English.

In 1722 a Peace Treaty was signed between the King of the Assateagues, Knosum, alias M. Walker, the King of the Pocomokes, Wassounge, alias Daniel and Charles Calvert, Governor of Maryland. It was agreed that this treaty would last to the "worlds end" and that hostilities and damages from former acts would be "buried in perpetual oblivion". The agreement reads that if an Indian killed an Englishman, he was to be brought to the Governor as a prisoner. That because the English could not easily tell one Indian from another no Indian should come onto an English plantation with his face painted, and that upon approaching the plantation they should lay down their weapons, whether guns or bows and arrows and call out. If they approached closer, then their weapons must remain behind. If an Englishman killed any Indian that came un-painted, called out and laid down his arms then the Englishman shall die. If the Indian and the English should meet accidentally in the woods, the Indian must immediately throw down his arms, and if they refuse they will be considered an enemy.

The privilege of crabbing, fowling, hunting and fishing would be granted to each Indian individually.

The Indian that kills or steals a hog, calf or other beast, or any other goods will be punished the same as and Englishman. Slaves and servants who runaway from their masters and take shelter in the Indian towns are to be returned by the Indians to the nearest plantation.

The Indians were not to make any new peace with the enemy of the Governor, nor make war without the consent of the Governor. If the Assateagues and Pocomokes killed any Indian subject to the Governor, it would be considered as great an offense as killing an Englishman. Strange and foreign Indians coming into the area were to be reported immediately to some person of note. For the expected protection the Indians were to receive from the Governor, the Assateagues and Pocomokes were to deliver unto the Lord Proprietor of Maryland two bows and two dozen arrows yearly on the 10th day of October.

"In 1742 a final treaty was made with the Assateagues, and signed by BASTOBELL, JOHN WITTONGUIS, JEREMY PEAKE and ROKAHAUM, Chiefs of the Assateagues and Pocomokes."

The once powerful Pocomoke-Assateague in 1678 began to gather and live at a single large town called Indian Town by the whites and known as Askiminokonson by the Indians. It was located near present day Snow Hill, Maryland.

In 1742, on the pretense of making an emperor, every Indian on the Eastern Shore disappeared into the marshes. Investigation revealed that a number of chiefs had become involved in a plot for a general uprising, fomented by an errant Shawnee chief, Messowan. The provincial government dissolved the empire, making the title of Emperor merely honorary, and placed each town directly under its own authority. Thereafter there was much agitation for permission to emigrate, and by the end of the decade a large part of the tribe had moved to the Susquehanna and become tributary to the Iroquois. This group moved slowly northward, and their descendants are now in Ontario, Canada. Of those who stayed in Maryland, one group lived on the Choptank reserve until 1798, when the State, having purchased all but 100 acres of their land, parceled out this remainder among the four or five families left. The last survivor of the group is said to have died some time in the 1840s. Another remnant of the tribe, retaining little of its native culture, has survived near Indian River in Delaware.